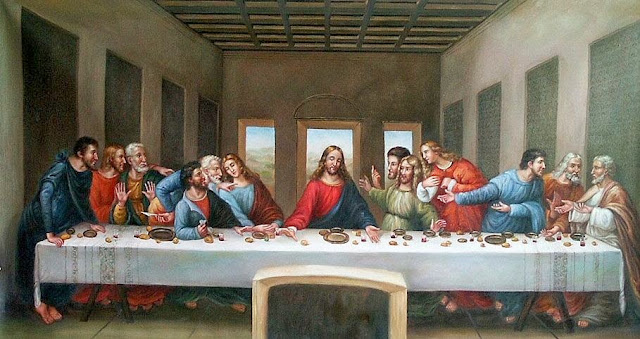

Eleanor de Toledo with her son Giovanni - 1545

Galleria degli Ufizzi - Florence

Agnolo di Cosimo, also known as

Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572), was an italian

mannerist painter from Florence. He became famous after receiving the Medici patronage in 1539, when he was one of the many artists chosen to execute the elaborate decorations for the wedding of

Cosimo I de Medici , Grand Duke of Tuscany, with

Eleanor of Toledo, age 17, daughter of

Don Alvarez de Toledo Viceroy of Naples. Don Alvarez, ruled Naples harshly upon the orders of

Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain and besides being his second cousin he was also one of his most trusted lieutenants. The marriage, between Cosimo and Eleanor, became highly attractive for the Medicis for a variety of reasons. First, Eleanor’s royal Castilian ancestors and relations with the Habsburgs provided the Medici with the royal blood they had lacked till then. Secondly, this association began the process of placing The Medici on the same footing as other European sovereigns and gave Cosimo a relief on the struggle he was endeavour in order to solidify and strengthen not only the Florentine State but also his own position as its leader . Through her father Eleanor also provided the Medici a powerful link to Spain, at that time ultimately in control of Florence.

I’ve been reading about Eleanor’s (Toledo 1522 – Pisa 1562) interesting life lately and it has fascineted me the way she became an influencial consort in the Court of Tuscany. Despite her initial unpopularity as a Spaniard, she turned to be loved by her people, founded many churches, encouraged the arts and became patron to many of the most notable artists of her time. Eleanor also revelead interest in business and agriculture helping to expand and increase the profitability of the vast Medici estates, serving as regent of Florence during her spouse absences, establishing her position as the first modern first lady. I saw Bronzino’s painting, for the first time, in Florence, at the Galleria degli Uffizzi and I became fascinated by her distinct and noble bearing and her stunning dress. Bronzino, was the court painter to Cosimo for most of the Duke’s long reign. His chillingly refined treatment of subjects is typical of the Mannerist esthetics. Eleonor’s portrait is a stunning example of the uncompromising detail and clarity which caractherized Bronzino’s work, and the portrait of Eleanor, dated 1546 is no exception. I found fascinating the dress. Luxurious and elegant with a fabric stylistically choosen for a spanish Duchess which influence, surely, affected fashion at that time.

As Joe A. Thomas quotes: “The costume and

fabric are given such importance that the painting almost becomes still life. The image of Eleanor in this dress became the equivalent of her state portrait and was repeated in various copies (

one of them at the Wallace Collection, in London). This elegant garment would not have been an everyday wear. Eleanor may have chosen her favourite, most elegant gown in which to be memorialized in her portrait. We know that this was a special gown to her not only because she was depicted in it in her portraits, but also because she was buried in it. When the Medici tombs were opened in the nineteenth century, Eleanor’s otherwise unidentified body was recognized because she was wearing this exact dress”.

Eleanor and Cosimo had 11 children and 2 of their sons, Francesco and Ferdinando, reigned as grand Dukes of Tuscany. The child in the picture is believed to be her second male son, Giovanni, who later became Bishop of Pisa and Cardinal.

Source: Joe A. Thomas and Wikipedia